A firsthand account of life as a remote student

September 16, 2020

I planned for a different semester than the one I’m having.

I was meant to move into my single in Swartz Hall the day before classes. Yet, one by one, each of my classes confirmed that they would not be meeting in person, as I had hoped, but rather online. So, I had to make the difficult decision to remain in New York, away from the University for, at the very least, the entirety of the fall semester.

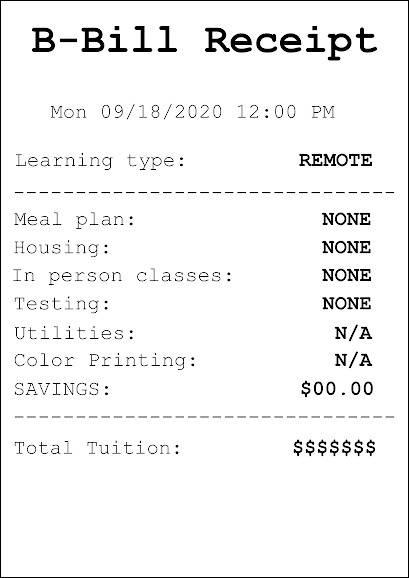

It is clear that I am among many others who elected to stay home rather than be on-campus this year, and I am also not alone in believing that tuition, by and large, should have been reduced for those who have to rely on video conferencing for their education. The University has been helpful in some regard concerning tuition, including a tuition freeze which will, as is stated on the University website, “mean a savings of more than $2,000 per student over our previously announced rate.” However, this is but a small solution for a larger issue.

In the spring of 2020, all current University students were sent home to finish the school year online. It was a substantially different experience that had many longing for the return of the authentic classroom experience — not the virtual class time mired with technical difficulties, disruptions and a general lack of focus to which we had become accustomed. That is not to say that the situation with remote learning is as grave this fall; many teachers and students who had once been forced to quickly adjust have now adapted better to the alternate form of teaching.

Nevertheless, even with improvements from the previous year, the experience of remote learning is profoundly different, though it is still being treated monetarily equal. The University is one of many schools that has refused to budge when it comes to a reduction in tuition, while also being one of the most expensive to attend in the United States. Yet it remains unmoving in its policy.

It is deeply frustrating, but also not unfounded. With fewer students on campus, the demand for housing has decreased as well. It is likely why the $700 meal plan has been entirely removed in favor of the now cheapest $1,400 option, which provides seven meals a week. As Terry W. Hartle, a senior vice president for the American Council on Education, stated in an article for the New York Times, “These are unprecedented times, and more and more families are needing more and more financial assistance to enroll in college… But colleges also need to survive.”

The higher frequency of students selecting remote learning, coupled with the ongoing pandemic has had many hindered the financial capabilities of the University. Study-abroad programs, in which the University touts that 49% of its students enroll, are canceled for the fall semester. That is a large source of income that the University no longer has access to — more so than other institutions, as the national average is at a much lower 10%. The necessity for greater public safety also enforces further spending towards, masks, cleaning supplies and other health products.

Little of the current situation is desirable, neither for the students who remained at home nor for universities like ours who are forced to make difficult decisions to stay afloat. According to Moody’s Investors Service, before the pandemic, nearly 30% of universities “were already running operating deficits.” While I am fortunate enough to have internet access in my home as well as a personal laptop, millions of other students are not nearly as privileged. Fourteen percent of students from the ages of 3-18 lack internet access at home, a greater struggle for remote-learning college students. This is a predicament where no one comes out the victor, and all are certain to struggle in. Eventually, we can hope for a return to a certain level of normalcy, but until then there is little for students and universities to do but adapt and hope to stay afloat.