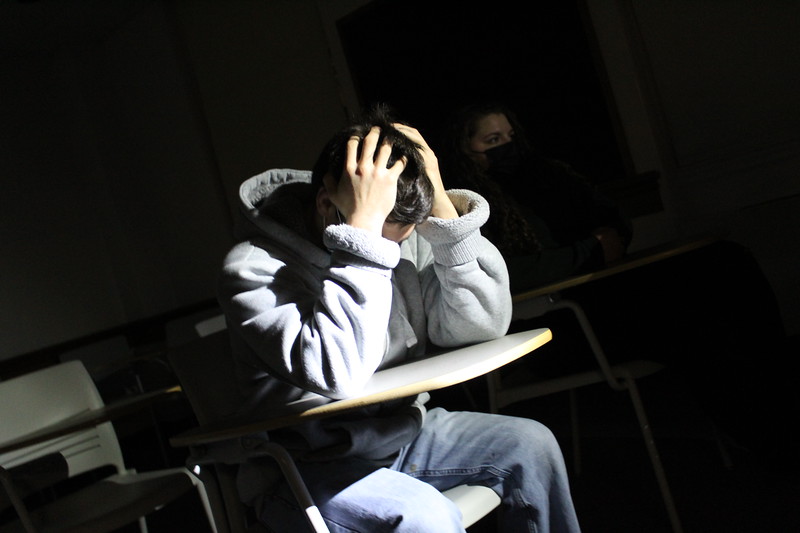

“They say they can’t meet with me for three weeks”: counseling center copes with mental health crisis

February 11, 2022

When the first MyVoice Survey collected diverse opinions of the University’s students in 2016, one message was abundantly clear: students felt strongly that the University should improve its mental health services. The belief was held by around 22 percent of respondents – more than one in five students. A follow-up action report by the University outlined responsive measures: hiring a counselor that specializes in eating disorders, increasing the volume of educational workshops and diversifying the offerings of their “Mindfulness Menu,” a series of activities intended to improve general mental well-being among students. Despite these efforts, 2019’s MyVoice Survey reflected no less discontent with existing services; instead, the percentage of students demanding better mental health services had climbed to 26 percent.

Since then, no publicly-available action report has responded to this data, nor a scheduled follow-up MyVoice Survey to gauge the current student reception on a clearly mounting concern; yet even without the available data, much is already clear about the current state of campus mental health services three years after the 2019 survey. As a deadly pandemic and simmering political tensions enveloped the United States, many students felt – and continue to feel – that current mental health resources are insufficient to effectively service the student population.

Director of Counseling & Student Development Center (CSDC) Kelly Kettlewell acknowledges the criticism. “I would be the first to say, I am so proud of the work coming out of this office, and I know that the number one concern for most students is ‘I don’t feel like I’m getting enough in terms of what would be supportive for me’. Both of those things are true,” Kettlewell said.

The director voiced the reality of the counseling department’s current conditions, explaining that a student with a “routine concern” may find themselves on a three-week waitlist. “It feels difficult to even use that word, because of course, when a student is reaching out, they might have been considering it for a long time […] it feels anything but routine, so I use that word carefully,” Kettlewell said. Those in higher-risk categories or situations, who require the immediate assistance of a counselor, can have their needs met far quicker. The vast majority of students vying for the department’s attention, however, are in the former category. “The counseling center is understaffed,” one anonymous response opined as part of 2019’s MyVoice Survey. “Whenever I make an appointment, they say they can’t meet with me for three weeks, which seems absurd.”

Little has improved in the intervening three years. The three-week waiting periods are not only the result of a higher volume of students hopeful to speak with the center’s counselors but by fluctuating staff numbers that, even at full capacity, remain lacking. “We’ve not always been operating at full capacity due to some staff turnover and open positions,” Kettlewell said.

For students, like sophomore Amanda Pennett, that waiting period can critically reduce the helpfulness and purpose of talk therapy. “It can be hard to access the strong emotions you were experiencing the moment you called when almost a month has passed,” Pennett said.

Junior Ava Rysman echoed similar sentiments. “I’ve had times too where I needed an appointment because I just really felt like I needed someone to talk to, and the long waiting periods stopped me from getting the help I needed, when I needed it,” Rysman said. The difficulties of aligning a student’s schedule with the center’s limited availability was but another concern Rysman stressed.

Kettlewell noted that the CSDC offered same-day phone appointments during weekdays to all students “for that touchpoint with [a] counselor.” The phone conversations, she explains, can at times be enough of a service for students that call in, while also serving as an opportunity for counselors to recognize higher-risk students who need to be brought to the Center faster.

But students like Pennett stress the importance of in-person appointments. “I really value the in-person one-on-one experience since I’ve been to therapy before, in-person and over Zoom, and I really think an in-person appointment is much more productive and comfortable,” Pennett said.

Of course, the University and the CSDC are not shy about the litany of alternative resources found online and readily accessible for all students. Following an affirmation just last year that the University is “committed to supporting your mental and emotional health,” the University announced its partnership with Togetherall, a free service where students could anonymously converse with others and receive support for their mental well-being. Yet despite its wide accessibility, local users are only a fraction of those that personally visit the counseling center; compared with 20 percent of students who visit in-person, only five percent use the virtual service. “It seems clear that the students’ preference is to have that one-on-one direct care, which we understand, we’re clinicians who want to give direct care, so we understand, we share value in that,” Kettlewell said.

A clear divide has been marked between the counseling center’s stopgap measures and the general disinterest of students in remote options. Yet despite the acknowledgments from the CSDC as well as the University itself, the administration has been slow to react.

Only late last semester did the University approve the counseling department’s full-time staff increase from eight members to 10; although an ongoing national search has continued, those positions remain vacant.

The reality at the University is, as Kettlewell often put it, that “the demand exceeds the supply.” Recent requests on the CSDC, which include outreach presentations in classrooms and training with student leaders, have been denied in order to ensure higher numbers of available counselors for student appointments.

Though no feedback forum currently exists for students to provide detailed responses about their time at the counseling center, Kettlewell noted that visitors are asked a series of questions following visits that reflect on their experience. In response to the question “did the counseling center help”, Kettlewell noted an 82 percent affirmative response, adding that the number of visits for students averages around five to six. While Rysman expressed disappointment over the initial meeting, an opinion also shared by Pennett, she expressed a more positive reception to later visits. “The initial appointment I didn’t think was that good, because they had to do a lot of question and answer stuff just to get to know you more. But I thought the appointments after that were really good,” Rysman said.

Much of this affirms one general criticism of CSDC resources; student concerns are less about the quality of services rendered, but lack of access to those services in the first place. Despite the supplements made to existing resources available on campus, Kettlewell still suspects that the number of students demanding services will continue to rise, continuing the trend illustrated by the last MyVoice Survey. “Obviously I would be guessing that that number would increase, if not stay the same. I would assume it’s higher,” Kettlewell said.

Kettlewell takes pride in the resources available at the University, though noting that certain deficits in services remain. “I think [the administration has] taken [concerns] very seriously by adding two additional staff most recently, and it’s not meeting the needs. They both are true,” Kettlewell said.

It has often been noted that the University’s services are consistent with its status as a rural campus with a small student population. Yet despite having a smaller number of students, other campuses have offered similar or even a greater number of services. Amherst College has half the students population of Bucknell but maintains a staff of fifteen who routinely communicate with students. Vassar College is two-thirds the University’s size, yet retains twelve staff members in its counseling center. Colgate University has seven full-time and four part-time staff members, with nearly 800 fewer students to support.

As important as the Counseling Center may be, Kettlewell notes that the burden can not merely rest on the center – also required is a reevaluation of how we perceive mental health. To her, the campus must develop a culture “that prioritizes peer-to-peer support in more real ways, that normalizes difficulty, that as a collective are able to tolerate some distress.” These sentiments were shared by Dr. Bill Flack, a professor in and chair of the University’s psychology department. “It’s important that we support and staff the CSDC as fully as possible, but at the same time we need to focus on making systemic changes in our campus community to prevent the kinds of problems that lead people to need counseling,” Dr. Flack said.

“Could you really staff a center to meet the demand?” Kettlewell asks in reference to the countless conversations she’s shared with her peers; “no,” is her rapid response.

“That would require potentially a staff, most staffs doubling or tripling in size, which is just unwieldy, that’s just often not what’s possible.” This is particularly grim news for students currently seeking timely mental wellness resources – like Pennett and Rysman.

“The fear is that the same thing would happen where time passes between the call and the appointment. That what I was dealing with has sort of reduced, so I feel like another waiting period would probably deter me,” Pennett said.

A desire for greater availability of CSDC resources nonetheless remains; those seeking mental health assistance are unlikely to be put off by its imperfections or dissuaded from reaching out when they are in need. A shift in campus culture, as both Kettlewell and Flack said, one that normalizes the mental concerns of its students, is indeed vital. But the truth remains that Bucknellians have continually called not for a reformation of the counseling center, but rather an expansion of its more personal resources.

“I think some people, myself included, get very in their heads and it just gets worse and worse everyday […] with a counseling appointment you could get out of that mindset, but without an appointment it just continues to get worse,” Rysman said.