Weather patterns: here, there, everywhere

March 3, 2023

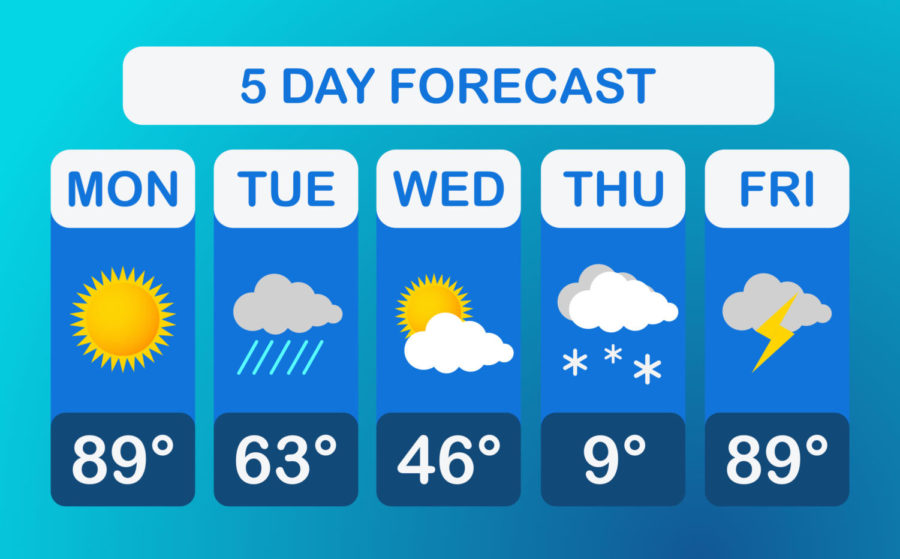

The weather coming back from winter break has been extremely irregular. Two weeks ago, we saw light flurries one day followed by almost 70 degrees the next. This pattern has continued as we go from cold to hot, puffer jackets to tees and back again. Besides being confusing and hard to keep up with, these weather swings are concerning. Weather impacts every aspect of our world, from the way we dress to health outcomes to economic and political (in)stability.

The New York Times reports that the recent New York City snowfall marks the end of the longest amount of time that New York City has seen without snowfall in the winter. While New York City and Lewisburg have seen a largely warm winter, other regions have seen more extreme weather in the other direction. Particularly, California and Michigan have experienced devastating storms that have put their residents at risk and, in many cases, without power.

First, it is important to address the adverse health impacts of these recent weather shocks. The Washington Post explains that the fluctuations that we have seen recently disrupt our “ecological systems” in a way that can “aggravate allergies, cause infections and worsen other more serious conditions, such as heart disease.” They further this argument with evidence from a Lancet Planetary Health journal study that draws a connection between these weather swings and higher rates of mortality.

There are also more indirect effects on our health. The White House uses a JPMorgan Chase Institute analysis to report that leading up to two more recent hurricanes, Harvey and Irma, household expenses shifted away from health care and into more immediate needs, including fuel and groceries. Therefore, weather shocks can even impact the access that we have to medical care in addition to the more direct physical distress and harm that they inflict.

In his 2018 IMF Working Paper, Sebastian Acevedo concludes that weather shocks can have grave consequences for political and economic stability. Particularly, Acevedo explains that in regions with warmer climates, “a rise in temperature lowers per capita output, in both short and medium term through… reduced agricultural output, suppressed productivity of workers exposed to heat, slower investment and poorer health.”

Moreover, the health outcomes we have observed above can impact a nations’ rate of economic growth. We should also consider the impact of extreme weather on the machinery or infrastructure that firms rely on for production. If a major storm destroys these integral inputs, then firms will have to put capital into reparations, which will have even further effects on output and potentially rates of unemployment. Additionally, Acevedo urges readers to consider how slow growth or even economic decline from these shocks can “provoke political instability, incite conflict or undermine governing institutions.”

We cannot continue to expect other people to step up. As we have seen, these fluctuations can impact every aspect of our lives, and as weather swings become more and more extreme, so do their impacts. Climate change and its impact on the severity of weather swings will not change if we don’t. What seems like the most important way to help right now is to consciously buy from and contribute to organizations that are taking the adequate steps to produce sustainably and reduce their carbon footprint. Just as weather impacts us, we impact weather. We are the problem, so we can also be the solution.