Beyond the Bison: Native cultural appropriation still persists in professional sports

September 27, 2019

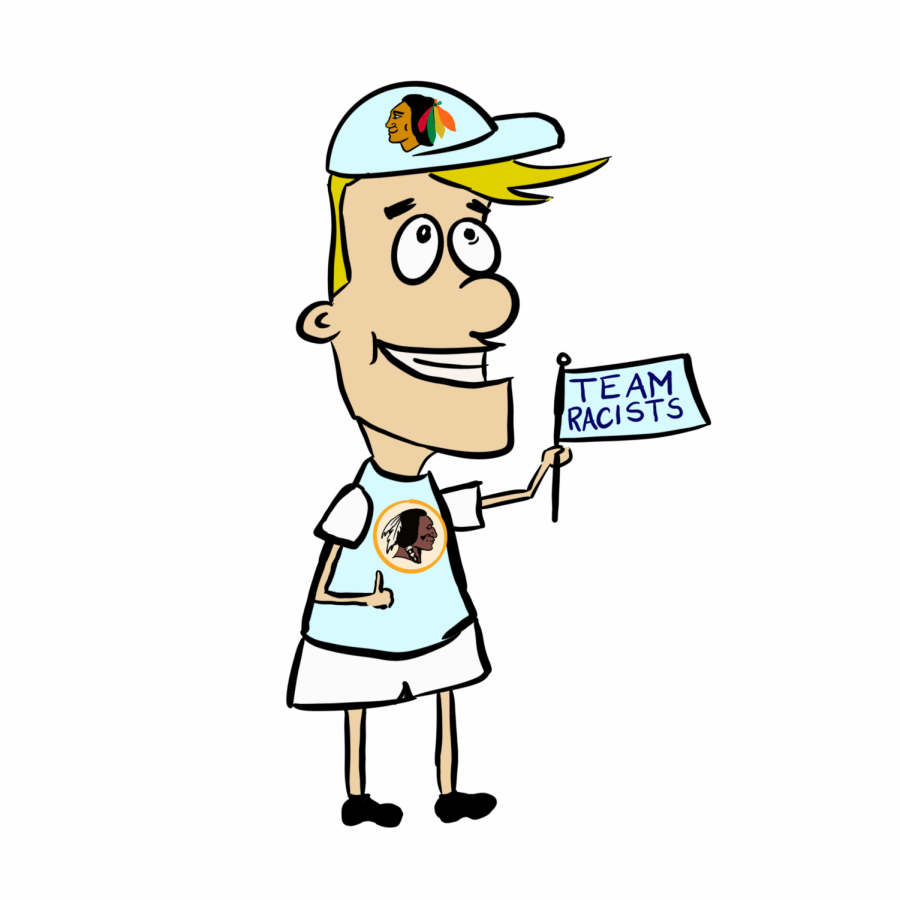

The Washington Redskins. The Kansas City Chiefs. The Cleveland Indians. The Chicago Blackhawks. All are multi-million dollar sports franchises, competing in the highest-caliber leagues in the world and exploiting derogatory racial stereotypes.

In 1968, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) launched a campaign to scourge popular culture and media, including sports, of dehumanizing and objectifying stereotypes of Native people and culture. Yet, in 2019 — 51 years later — our American professional sports leagues still allow the continued use of appropriated Native mascots.

The most prominent example is that of the Washington Redskins. In fact, “redskin” is a dictionary-defined racial slur. According to the Change the Mascot campaign, the word is not simply a classification of skin tone. Rather, it refers to the bounty hunters who would be paid for the number of Natives they killed and skinned. Backed by studies by the American Psychological Association, NCAI claims that harmful mascots such as Washington’s pose negative psychological, social, and cultural consequences for Native Americans — regardless of their intent. The U.S. Trademark and Patent Office has gone so far as to call it “a derogatory slang word.” Writing the word on someone’s home constitutes a hate crime. Why does our society allow a premiere sports franchise to call itself by a name that is employed in hate crimes?

In the past, many have defended such cultural appropriation by claiming that Native Americans are not offended by the use of such terms. For example, a 2004 Associated Press survey of almost 800 people who identified as Native Americans has been cited to demonstrate that 90% of Native Americans believe that the name “Redskins” is not offensive. However, newer studies conducted by sociologists, with rigorous methods to confirm Native ancestry, show that the majority (67%) perceive it as a racist word.

In the midst of this, we should recognize that some progress has been made. According to the NCAI, since 1963, no professional franchise has been newly established using a racially-stereotyped mascot. Additionally, in 2005, the NCAA put policy in place to remove such mascots. In the past 35 years, two-thirds of “Indian” references in athletics have been quashed, among them Dartmouth College and Stanford University. (Still, over 1,000 cases remain.) This year, Maine was the first state to ban Native American mascots in school. And at the start of the 2019 season, the Cleveland Indians removed the image of Chief Wahoo, a stereotypical Native figure, from their uniforms and all signs at their ballpark.

Suzan Shown Harjo, of Cheyenne and Creek ancestry, is a leader in this “war on words,” says The Washington Post. Her protests and lawsuits in pursuit of banning Indian nicknames and mascots in sports have paved the way for a sort of cleanse of these references in athletics. For this, along with various other Native activist roles, President Obama awarded Harjo with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2014. On Sept. 20, 2019, her story was honored at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.

Yet the football team in the same city still meets her protest with vocal resistance. In a 2013 USA Today interview, Redskins owner Daniel Snyder stated, “We’ll never change the name. It’s that simple.” NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell echoed in 2018 that the league would not pressure the Washington, D.C. organization to change their name.

As Harjo put it to ESPN, Natives have had their homes taken away and their identities have been stolen for profit. “It’s adding insult to injury,” she said.

Our reticence on the matter can be perceived as an artifact of long-standing white settler colonialism in North America. We can misrepresent survey findings, we can claim free speech rights, and we can adhere to the views of disinterested fans, or we can make one courageous cultural change that makes a whole community of Americans feel more respected in their own country. Certainly, fans can, and should, hold their idolized athletic organizations to higher standards than they currently are.