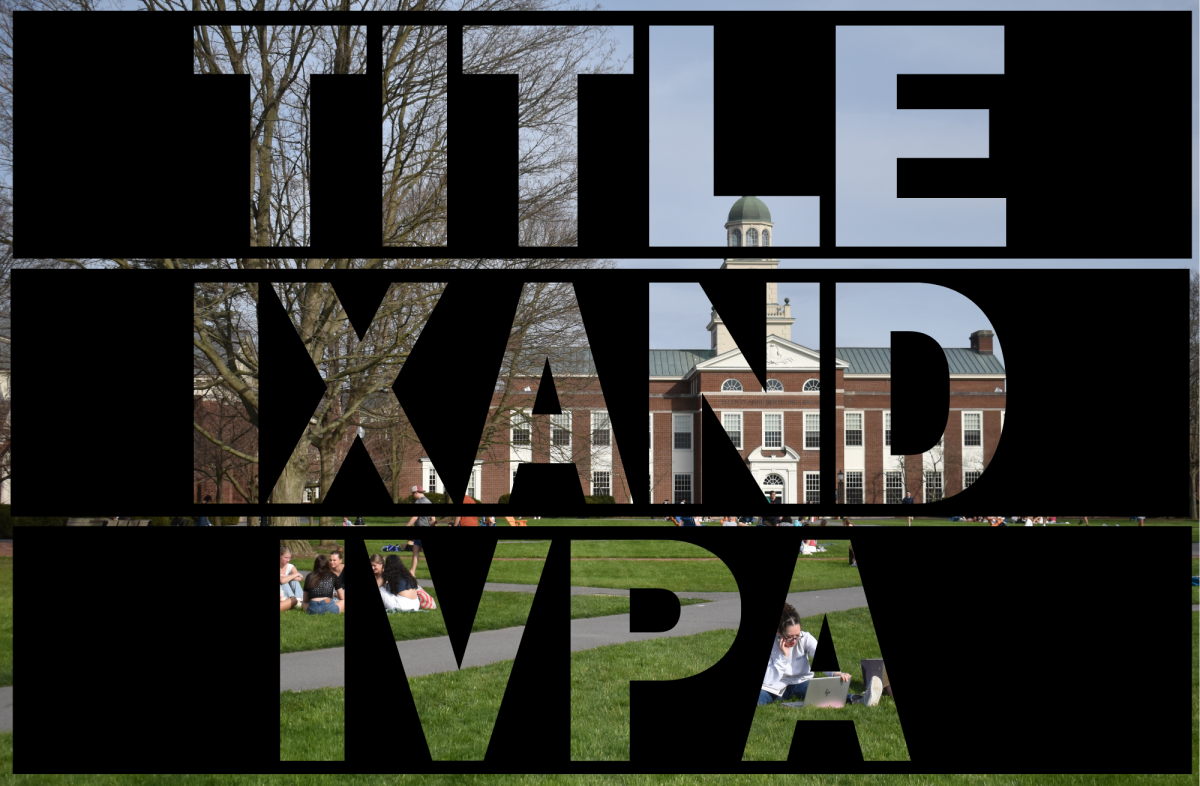

Vocationalization versus Liberal Arts: A historical look at the debate

March 3, 2023

What attracted you to Bucknell? Did you want a school with Christian professors? Did you desire a classical curriculum with training in Latin? You are probably smirking at these suggestions. Although they may seem laughable, the Bucknell University Bulletin from 1904 marketed the school’s religious community and classical curriculum to attract prosperous Protestant students. In the present day, Bucknell attempts to admit students of different backgrounds to form a diverse student body.

The university advertises the management and engineering schools to show they offer professional training. Bucknell simultaneously depicts itself as a liberal arts college, appealing to students who want a breadth of learning. The university’s marketing of vocational and liberal arts education is somewhat contradictory. Many universities have similar conflicts as they debate whether the purpose of education is to professionalize students or develop them into moral citizens. While we think of this deliberation as new, it has been ongoing since the birth of higher education in America. Let us examine the history of universities and relate the past to our current circumstances as Bucknellians.

For years, scholars have debated the purpose of education. During medieval times, the Scholastic movement deemed logic vital to self-cultivation. Humanists during the Renaissance valued rhetoric, believing students would absorb moral philosophy by studying antiquity. Both Scholasticism and Humanism influenced the founding of Harvard University (1636). Harvard also reflected the beliefs of its Puritan founders. The main purpose of the institution, along with other colonial schools that followed, was to use classics to train men to enter the ministry, law or medicine. The schools dictated a rigid set of courses because they lacked funds to hire more professors to teach electives. The fixed curriculum also conveyed that only prestigious classical courses were suitable to develop students.

In the 1800s, American schools began to emulate the German model of education. Classics was the first discipline to professionalize. Scholars took a systematic approach to classical philology. German methods of seminars and lectures replaced drilling. The German influences also turned academia into a career. Professors became specialized and started to publish research, gaining them more prestige and pay. The German model of education encouraged scholars to produce new knowledge, instead of solely studying the ancients.

In 1876, Johns Hopkins established itself in the German style and created majors and minors. As a research institution, the school valued knowledge production. In contrast to how the students of Johns Hopkins followed tracks, Harvard President Charles W. Eliot started the Free Elective System to reimagine classical education, encouraging students to take courses that suited their interests. By 1897, all courses were electives except for one English composition class. The lack of requirements often prompted students to enroll in the easiest courses possible, lowering the rigor of their education.

Other schools imagined education without classics. Wesleyan offered the B.S. in 1838 as a degree that didn’t require a full classical education. The B.S. lacked the prestige of a B.A. because it didn’t follow the traditional educational model. In 1875, Edward McKnight Brawley was the first Black student to graduate from Bucknell. He earned a B.S. because, at the time, a B.A. required knowledge in Latin and Greek. The language requirement shows how students of marginalized identities were limited to a less respectable education.

While the old educational system was exclusive, vocational education offered learning to more people. With Andrew Jackson as the first president without a college education in 1829, America was becoming increasingly populist. The Morrill Land-Grant Acts (1862) established colleges on government land to train students in agriculture and the mechanical arts. The acts both increased professionalism and opened higher education to more students.

Enemies of specialization favored liberal studies and crafted general education courses. In 1947, president of the University of Chicago, Robert Maynard Hutchins, founded the Great Books program to create a common curriculum. He praised Greece and Rome as the start of western civilization. While schools do not follow the Great Books program today, its legacy remains. In 2017, students at Reed College protested the compulsory humanities course for first year students. The protesters argued the class prioritized voices of antiquity and they did not see themselves in their education. The demonstrations led to changes in the course syllabus, which now reflects more racially diverse voices.

Higher education in America has evolved since the founding of Harvard. Not only are the students more diverse, but the education has changed from classical to including a variety of majors. The purpose of education remains subjective as students may attend the university to gain professional training, obtain a breath of learning or a combination of both. After reading this piece, you may be wondering what I myself study. As an English and Classics major, I choose to study the humanities to gain an expanse of knowledge. Although I do not have a vocational major, I believe my communication and critical thinking skills are valuable traits that will hopefully help me find a job in the future. No matter your reasoning to attend Bucknell, contemplate what you want from your college experience and take ownership of your learning.