Chanel Miller–writer and artist, as well as self-proclaimed lover of strawberry ice cream and figs, senior dog person, eldest daughter, child of immigrants, winner of best personality in high school and also a victim-survivor made famous for her victim impact statement released under her court pseudonym Emily Doe–spoke to campus on Tuesday April 9th about bravery, art, self-expression and healing.

Miller opened her talk with a reading from the afterword of her critically-acclaimed book “Know My Name: A Memoir.” In the portion that Miller selected, she discussed her decision to release her name along with the publication of her book, which hadn’t been promised in the contract.

“I don’t know that there was ever a day I firmly decided. I did know that I wasn’t going to let the fear of what men might dictate what the rest of my life was going to be,” Miller began.

Later in the talk, Miller discussed that coming forward was never one single action, it happened in stages. When she first began getting requests for interviews, it was frustrating as interviews seemed all too similar to interrogations, which had been a traumatic part of her court experience. In describing the court experience of a different sexual assault victim-survivor, Lindsay Armstrong, Miller noted that “guilty convictions don’t undo damage.”

When she did begin to feel the courage to give interviews and decide what she wanted people to hear and who she was going to speak to, Miller wished she could speak to Armstrong, but really to all victim-survivors who had similar victim-blaming experiences: “I was going to tell her we get to wear whatever the f*ck underwear we want.”

Miller described herself as taking “baby-steps” as she built the courage to do the next step in claiming her story publicly and bringing more of herself into the public light.

This was not always a straightforward process. In court, her psychological boundaries fell; anything that was asked of her, she felt she had to give up. But in the media and “the real world,” Miller learned that she could set boundaries, and that she didn’t owe anyone anything. Whereas court felt like “ripping [her] guts out,” her first media experiences in which people curated environments for her and were careful with her showed that she and her story are valuable.

Miller also talked about the experience of being a public figure while balancing recovering from her own trauma and the pressures created by that recovery. As a public survivor, she was open to hatred and love, but described the love as “isolating,” because “people may put you on a pedestal or idolize you, and then you feel like you’re respected because you’re a good victim, or a polished, articulate person. And then you go home and think, would they love me if they really understood me or how flawed I am?”

This feeling resonated with her experience in court, during which she resented being upheld as a good victim as proof that she didn’t deserve harm. The court system made her feel like a “criminal” for having done things like blacking out before, as though any mistake made her undeserving of care or respect. Given public eyes and praise, Miller initially felt she had to “walk a tightrope” of what she could share, but now has sought to be liked for “being a messy, flawed person,” and to not have to live up to expectations that idealized her.

Miller also noted how unique the response to trauma is for every person, which makes giving advice on recovery challenging. For example, her community’s response to suicides as she was growing up caused her to internalize that “you are to grieve in private,” and then affected how she responded to her assault. Understanding human complexity allowed her to forgive herself for how she reacted and grow in her understanding when others react differently.

Similarly, she discussed that friends and family respond to learning of someone’s trauma and support survivors differently. Her advice for anyone who knows someone who has been assaulted was, even if you don’t know what to say or do, to “never underestimate the power of presence. Somebody’s silence and inaction can be incredibly painful…Inaction is an action. That silence will be felt.”

Moderator Kristin Gibson, Associate Director of Interpersonal Violence Prevention and Advocacy, then shifted the conversation to Miller’s experiences with art and self-expression as tools of recovery.

Miller stated that writing her book offered a chance to revisit memories where she felt out of control, “like a two inch figurine in this courthouse, where I was trapped for hours and hours,” and instead have power over them as she retold them herself. “When I write,” she stated, “I become the creator of the entire universe.”

Additionally, in crafting visual metaphors at her editor’s suggestion, Miller was able to make experiences understandable to readers or listeners who may not have had the experiences she’s describing. She compares cross-examination to having her shoes tied together and being asked to run, offering others a perspective to empathize with, despite not being survivors themselves.

Writing a memoir when she was between the ages of 24 and 27, Miller also learned the value of her own point of view and perspective. She told attendees, “if you take away anything, it’s to honor your point of view and bring it into any field that you enter.”

Miller left the audience with the following: “I hope that you allow yourself grace, forgive yourself. I was made to feel punished for a lot of party qualities in my life that are not criminal, they’re just human. You’re allowed to grow up and make mistakes, that’s just part of the deal.”

The event closed with a Question & Answer session, in which students, staff and faculty asked questions of Miller.

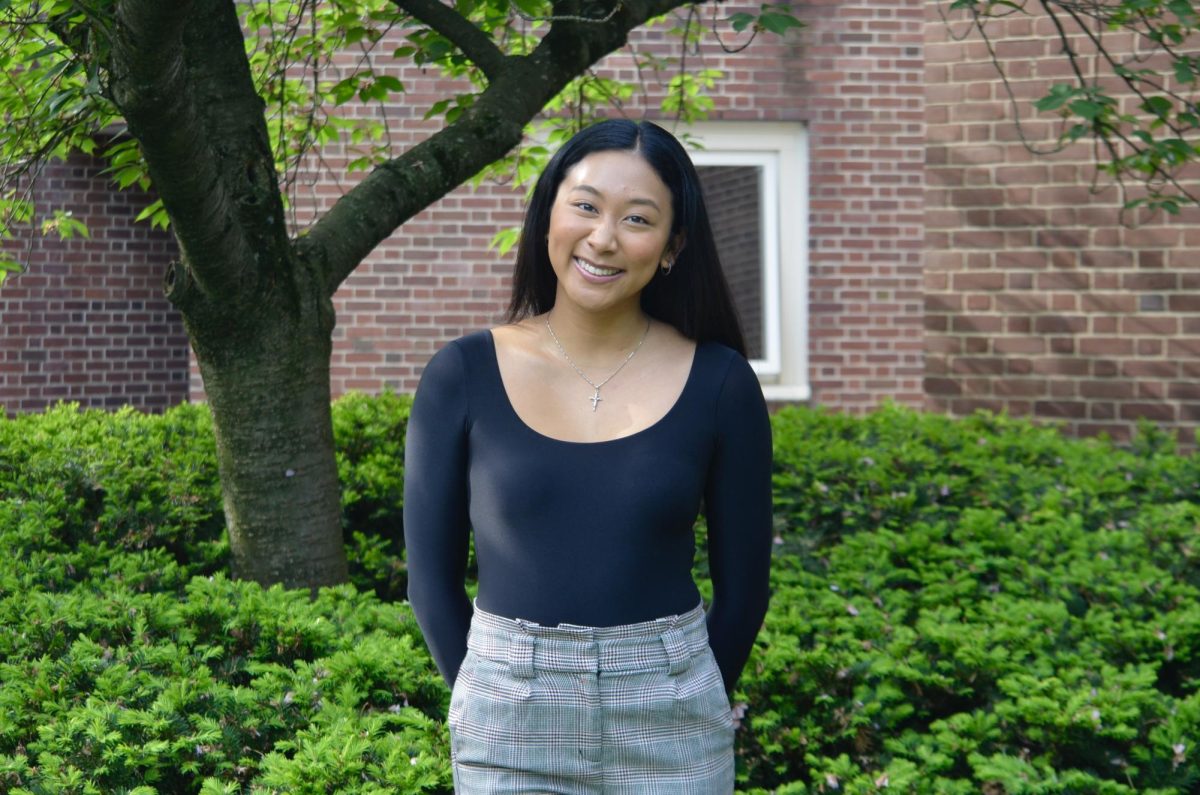

Ericka Anghel ’25, Speak Up President, was the first to ask a question. She described Miller as “incredibly personable, funny and so well-articulated,” adding “I was blown away by the wisdom, bravery and kindness that Chanel offered to us. I left the event feeling inspired and hopeful.”

Erica Delsandro, Associate Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies, asked about rape culture and the role of bystander intervention in her own story, being particularly “struck by Miller’s generosity in her discussion of bystander intervention. She was discussing the Swedish graduate students who interrupted her assault and stopped her assailant. In the context of her retelling of that part of her story, she offered the audience a choice: one could choose to be like the Swedish graduate students or choose to be like her assailant. When presented in such stark terms, the choice seems simple and obvious. And yet, many within our community struggle with this choice.”

Delsandro also added “it was terrific to see so many students in the audience at Miller’s talk, especially such a robust turnout by members of Greek life. And while it was encouraging, I could not help but also consider how many victim-survivors were likely sitting in proximity to their assailants, how many targets of gender-based and sexualized violence were sharing space with their perpetrators. Gender-based violence and sexual assault saturate our community and so many students’ lives are irrevocably shaped by such traumas. As a community, we need to reckon with this reality.”

“I really enjoyed how personable she was while discussing an event that very much dehumanized her,” Kaitlyn Segreti ’25 stated. “It generated a sense of emotional vulnerability that didn’t paint her as a faultless victim or label her attacker as an irredeemable monster, but rather reflected her honesty as a person with flaws of her own. In doing so she demonstrated that victim survivors of sexual assault are allowed to be themselves and shouldn’t have to feel the pressure of constant perfection for gain others’ respect.”

Miller’s talk was one of many events happening in April for Sexual Assault Awareness Month. Other events include What Were You Wearing? April 12th at 4:30 p.m. in Walls Lounge, I <3 Female Orgasm April 16th at 5:00 p.m. in Trout Auditorium and Denim Day April 24th.