Recent grad takes to the Appalachian Trail for 2,200 miles of “wilderness therapy”

September 1, 2016

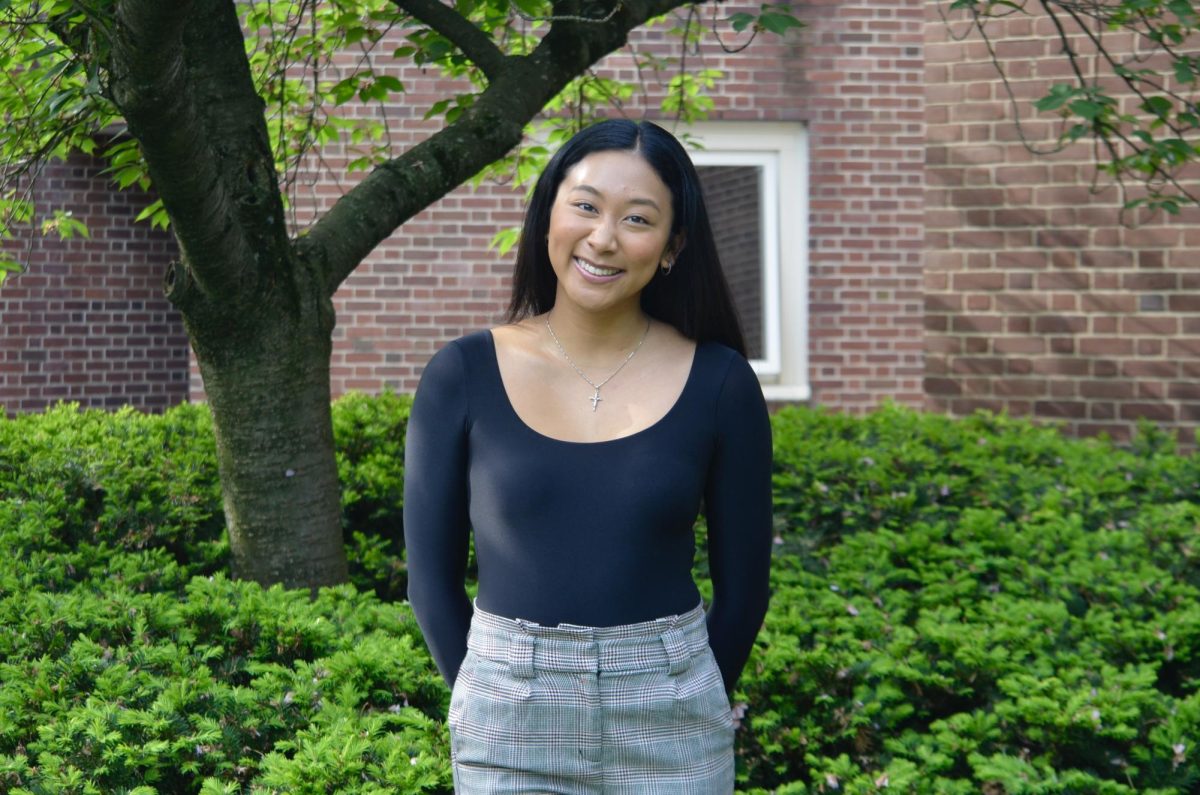

Collegiates often regard graduation with anxiety, as they try to imagine what life will be like without the annual return to their familiar, comfortable routines at school. But it would likely be difficult for most students to imagine themselves carrying nothing but a backpack filled with Pop-Tarts and a tent, walking up to 31 miles in a single day, a mere week after graduation. The same cannot be said for Ken Inoue ’16, who embarked on a 2,189.1 mile journey through the Appalachian Trail on June 1 after graduating from the University on May 22.

Inoue, also known as his trail name, Popper, began his hike in Tunkhannock, Pa. and reached Maine 1,000 miles and two and a half months later. After taking a week-long break, relaxing, and catching up with friends, Inoue returned for the second half of the hike on August 24.

Inoue decided to hike the trail around three years ago. He was unaware of his penchant for outdoor activities until he arrived at the University and experienced the pre-orientation program, BuckWild, along with a subsequent trip to Chile, where he hiked for five days in the Andes.

The Appalachian Trail spans 14 states from Georgia to Maine, and sees about 3 million visitors a year. While most prospective hikers spend months training for the long walks through occasionally treacherous terrain, Inoue did nothing to prepare. He spent the time leading up to his departure relaxing and watching TV. With 1,000 miles completed, Inoue now boasts defined leg muscles and has lost 15 pounds since June (despite a steady diet of Pop-Tarts, candy bars, bagels, and pasta).

But improving physical fitness was never Inoue’s goal. After spending a portion of his college career battling mental illness, Inoue sees the hike as his form of “wilderness therapy.”

“Honestly the moment I left [college], it’s been calling me. Like, I gotta get out of here,” Inoue said.

On the trail, Inoue was forced to adopt a far simpler life, one without everyday luxuries such as beds and showers, but also one without distractions and social pressures.

“There’s nothing else to do but walk. It really prioritizes your day,” Inoue said.

His “hobo experience” has enlightened him as to the values of minimalism which he plans to integrate into his daily routine when he returns home. In terms of societal pressures, Inoue realized that he would probably never see any of the hikers he met again, so he felt no need to “put on a mask. I can just be who I am,” a mindset he also plans to maintain in his future interactions.

Inoue also claims to have had his faith in humanity restored through his experiences with something referred to in the hiker vernacular as “trail magic,” when strangers, often anonymously, offer help to hikers. For example, in New York, temperatures were blazing, and the heat dried up many of the water sources. Strangers who live near the trail have a practice of leaving gallons of water on the side of the road for hikers to come across, which Inoue says “feels like finding a treasure chest.”

Inoue says his new outlook on life is worth all the trials and tribulations he has endured thus far—and there were many. Aside from the obvious physical difficulties that go along with hiking from sunrise to sunset, there were also mental struggles.

“The first month is like a physical battle, you’re getting in shape, hiking every day, waking up at early hours … after that, once your routine is set, it’s just all mental,” Inoue said.

He can point to two prominent moments when he wanted to quit, one of which occurred while he was hiking through New York, the hottest leg of the trail. He thought to himself, “What am I doing out here? Like I’m walking 20 miles a day, that’s cool, but I’m not making any money … I’m not really moving forward.”

Despite those moments, Inoue claims he has never considered skipping the second half of the trail. In fact, he is genuinely excited to return. His week-long break has already exposed him to a few of the difficulties of assimilating back into society, which will likely become even more pronounced after another two to three months in the wilderness. These difficulties include adjusting to sleeping on a mattress again instead of rocks and twigs and passing strangers on the sidewalk and not expecting them to say hello (something he says always happens on the trail).

When asked how he plans to celebrate his completion of the hike, Inoue said, “Maybe a pedicure.”

He does have two jobs lined up: one of which he is really passionate about—working with at-risk youth in the Everglades—and one of which he acknowledges goes against his new distaste of urban capitalism, but may be necessary for his financial stability—working as a market researcher in New York City.

Inoue also hopes to get involved with marathons and even complete the remaining trails that comprise the Triple Crown of Hiking: the Pacific Crest Trail and the Continental Divide Trail.